Read more at architecture.com.au

Category: Uncategorized

2020 Australian Institute of Architects Dulux Study Tour Winners

Read more at architecture.com.au

2020 Australian Institute of Architects Dulux Study Tour Shortlist

30 emerging architects have been shortlisted for the Institute’s Dulux Study Tour. Five individuals will be selected for their contributions to architectural practice, education, design excellence and community involvement. In 2020, the winners will visit Tokyo, Berlin and Madrid where they will experience first-hand some of the best architectural sites and practices.

AND THE 2020 INSTITUTE’S DULUX STUDY TOUR SHORTLIST IS…..

Sarah Ainsworth, Arklab Architecture (QLD)

Qutaibah Al-Atafi, Self-employed (Vic)

Evie Blackman, NAAU Studio (Vic)

Samuel Bowstead, James Davidson Architect (QLD)

Robert Davidov, Davidov Architects (Vic)

Cameron Deynzer, Andrew Burges Architects (NSW)

Hugh Feggans, AYCH (Vic)

Nicholas Flatman, Self-employed (NSW)

Matt Goodman, MGAO (Vic)

Daniel Hall, Bligh Graham Architects (QLD)

Jamileh Jahangiri, Cox Architecture (NSW)

Yang Yang Lee, Philip Stejskal Architecture (WA)

Adam Markowitz, Self-employed (Vic)

Sam McQueeney, Vokes and Peters (QLD)

Yvonne Meng, Circle Studio Architects (Vic)

Nicholas Putrasia, Kerry Hill Architects (WA)

Nick Roberts, John Wardle Architects (Vic)

Simon Rochowski, studioplusthree (NSW)

Kristina Sahlestrom, Luigi Rosselli Architects (NSW)

Christopher Schofield, Studio Schofield Architecture + Interiors (QLD)

Madeline Sewall, Breathe Architecture (Vic)

Tahnee Sullivan, Sullivan Skinner (QLD)

Madeleine Swete Kelly, Blight Rayner Architecture (QLD)

Tamarind Taylor, Conrad Gargett (QLD)

Camilla Tierney, Bates Smart Architects (Vic)

Ksenia Totoeva, Tonkin Zulaikha Greer Architects (NSW)

Bek Verrier, Bence Mulcahy (Tas)

Kirsty Volz, Toussaint and Volz (QLD)

Elizabeth Walsh, Cumulus Studio (Tas)

Keith Westbrook, Cumulus Studio (Vic)

Congratulations to all those who were shortlisted! The jury were certainly impressed with the high number of quality entries received. If you didn’t make the shortlist, we strongly encourage you to enter again next year as the program continues to grow with new and exciting destinations on the horizon.

Now for Stage 2….

Entries open for the 2020 Institute’s Dulux Study Tour

Celebrating its 13th anniversary, the 2020 Institute’s Dulux Study Tour is your opportunity to be part of an exciting and coveted program that inspires and fosters Australia’s next generation of emerging architectural talent. Winners will embark on an exciting architectural international tour where they can experience firsthand some of the best architectural sites and practices.

Entry into the 2020 Dulux Study Tour is a two stage process:

Stage 1

To enter, entrants are required to submit their answers to four nominated questions, their contact details and details of their employer via the online entry system.

Stage 1 submissions close at AEDT 5:00pm Monday 14 October 2019.

Late submissions will not be accepted. Entrants’ answers to the nominated questions will be judged, and shortlisted entrants will be notified to enter into Stage 2.

Stage 2

Shortlisted entrants must upload via the online entry system an A4 document that includes: an employer reference, resume (maximum two pages), portfolio of works (maximum of four pages). Submissions for stage 2 will be open from Thursday 17 October 2019 when shortlisted entries will be notified of the outcome. The closing date for Stage 2 is 5:00pm AEDT Monday 18 November 2019.

2019 Dulux Study Tour: Thanks for the laughs, tears, and tarts

The 2019 Dulux Study Tour has been a jam-packed whirlwind tour of fun, reflection, inspiration, and a bit of emotion thrown in for good measure. An experience, I believe, will take us time to understand the full value to our careers.

From the moment we stepped off the plane and onto the timber parquetry floors of Copenhagen airport, we were surrounded by architectural and design inspiration, including a sighting of Bjarke Ingels at the airport.

The tour structure of visiting three cities, fifteen practices, and countless buildings and spaces over ten days meant that our conversations compared the differences and similarities. Comparisons were made to our own practices in Australia and between the individual cities of the tour. This is something we all do when travelling, but having the focus of five architects put the discussions into overdrive. From Copenhagen’s sense of publicness, to London’s palatable energy, and historic Lisbon – we discussed our initial impressions of the essence of each city. What opportunities are there for us to learn from the positive and negative aspects of these places? What can we learn from the experience of the various architecture studios we are visiting?

Our analysis and reflection of cities also filtered into our own relationships as we quickly began to form friendships. Conversations about our Zodiac star signs, Myers–Briggs type indicator, and love languages were intertwined with questions of how we create, protect, and improve culture. Over dinners, drinking, and dancing we were able to enjoy the cities, and each other’s company, as regular tourists.

Past Dulux Alumni have told us how awesome the study tour is. However, we all felt humbled by the generosity of Dulux and the Australian Institute of Architects. Generosity is a theme of the tour as the design studios opened their doors and minds to our questions.

The experience has been made unforgettable by everyone on the tour. My fellow winners: Alex Smith, Carly McMahon, Jennifer McMaster, and Phillip Nielsen.

We were joined on the tour by our Dulux hosts, Anurita Kapur and Caroline Field. They have a real passion for supporting and encouraging emerging architects. They wanted us to get the most from the cities and practices we visited. This extended to embracing the 2019 Eurovision Grand Final in London, and fuelling our obsession with Pastel de nata in Lisbon. Linda Cheng, of Architecture Media, inspired our Dulux Study Tour band photos, something we have become accustomed to, and by the end of the tour we were actively looking for our own awkward family photo opportunities. In the hours following the formal end of the tour, and without the steady guide and perfectly timed WhatsApp messages from Mai Huynh of the Australian Institute of Architects, the Dulux Study Tour winners had missed trains, taken a taxi to the wrong hotel, and struggled to open doors of an Airbnb. A sign of Mai’s commitment to getting us where we needed to be when we needed to be there.

The professional and life experiences of everyone on the tour made the ten days more than a study of architecture and practices. It was a much broader conversation of the role and value of design in our society, and how each of us can contribute to culture. A conversation that we will continue to have with each other as we return to reality.

– Ben Peake

Lisbon day 3: A Bit Like Chef’s Table

Today was marked by a series of practice visits where, towards the end of the day, a key theme emerged, courtesy of ARX Arquitectos’ director, José Mateus.

During our visit, José compared a career in architecture to a narrative arc on the popular TV show, Chef’s Table. These chefs are passionate about what they do, but also experience considerable challenges in their careers. As José stated: “There is a common aspect to all of these chefs, which is a capacity to resist all sorts of troubles, and I think this same thing is crucial to young architects.”

To pursue a career in architecture, José believes, you need vision, strong convictions, and plenty of resilience. These are qualities we witnessed across all three practices today, beginning at Embaixada.

Embaixada is a small practice with what, for me, is a very familiar story: three architects started their studio “from scratch” shortly after finishing university. Fast forward to today, and Embaixada have completed elegant projects across Europe and Asia.

Embaixada’s vision is deeply embedded within their studio’s brand. Embaixada, which translates to mean “embassy,” is best defined by the practice’s logo, a creature with three heads of a tiger, a snake and a flamingo.

Each animal represents a different personality: the tiger is strong and imposing, the snake sneaky and strategic, and the flamingo sensitive and delicate. It’s a great metaphor for the many roles we need to adopt as architects. For Embaixada, it has helped define its design process and collaborative model for eighteen.

After a quick round of Portuguese tarts – facilitated by our formidable guide, Embaixada’s Cristina Mendonca – we knocked on the door of Bak Gordon.

The studio’s director, Ricardo Bak Gordon, showcased the practice’s calm and consistent work, which exhibits the best qualities we’ve witnessed here in Lisbon: a sensitivity to context, respect for history, and an unassuming use of materials. Sitting through their project slideshow was a veritable feast of excellent work, and I left with no doubt of this studio’s success.

Our last stop was at ARX Arquitectos, where we sat down with José Mateus. Over the next hour or so, he shared his story with humility, honesty, humour and grace.

ARX Arquitectos started in 1991, when José was twenty-eight and his brother and co-director, Nuno, was thirty. At the time, they cracked opened a bottle of Moët, and began working out of a modest, 50-square-metre apartment. Their story screamed of optimism and, as the practice began doing more projects, they thought: “Wow – we are going forward so fast.”

But, of course, every hero – or heroine’s – journey comes with its setbacks. Here, José speaks of the 2010-2011 economic crisis as period when business got tough. During this time, the studio had no work and 50% of Portuguese offices closed. To survive this downturn, the studio diversified its portfolio and began working in new sectors and locations.

Today, 90% of the practice’s work is in Lisbon, and ARX supports a stable team of twenty people. Recently, the studio has shifted to a four-day working week, allowing people to adopt more balanced lives. José also spoke with pride about the fact that he pays all of his staff proper wages, in resistance to the unpaid internship culture that proliferates our industry.

I’ve always found an enormous amount of comfort in hearing other people’s stories. A bit like Chef’s Table, they remind us that we all make mistakes and experience difficulties as we strive for excellence. They also remind us to act with courage, confidence and conviction, knowing that these qualities are ultimately rewarded.

As we went on, José continued to dispense the wisdom he’s learned across twenty-five years of practice. Speaking about the studio’s work, he described how “we have very clear ethics and values, and we don’t accept things that can damage the city.” He also described his involvement in politics and public life, which he noted as “a privilege and a pleasure.”

As we wound up our final day, I reflected on the fact that myself, Ben, Phillip, Alix and Carly are only at the beginning of our own narrative arcs. As I’ve learned on this tour, we are all passionate and purposeful, with goals and dreams and projects to lead. Yet, we’ve also experienced setbacks, and missteps, and moments we regret. Hearing the stories of these three practices offered me – and all of us – a lot of hope and solace. We all left with more lessons under our belt, knowing there’s so much more to strive for.

– Jennifer McMaster

Lisbon day 2: Castles and concrete canopies

I would be remiss to start this post without acknowledging the group’s overwhelming obsession and hunger for Portuguese egg tarts. As such we sent Ben out on his morning run with a mission to bring back a box of tarts for all. Feeding time at the zoo occurred in the hotel lobby before we boarded a bus for the walking tour of Lisbon.

Driving north we stopped outside a monolithic form surrounded by a Miesian pavilion at the lower levels. This project by Gonçalo Byrne Architects and Barbras Lopes Architects is a restoration of the Thalia Theatre ruins. The concrete exterior of the building is an austere shadow of the original 1825 theatre that provides structural support to the ruins within. Entering from the back of the building through the contemporary addition a small door way opens into the theatre revealing the crumbled stone walls of the original 1825 building. I couldn’t help but contemplate the contradiction of the exterior and interior and how this type of architectural response would be received in Australia’s pursuit of replicating heritage to complement heritage. While this renovation is a contemporary work there are moments when the marriage of old and new is so well executed that it is hard to tell which is which.

The next stop on our “walking” tour by bus was the site of the Lisbon Expo where we became quickly distracted by a pond of water and the reflections of light cast on to the soffit of a small canopy. Architects… what more can I say?

The group paused for a moment and enjoyed a coffee in the new extension to the Oceanario de Lisboa. Our amazing tour guide Rodrigo Lima elaborated that the theme for the Lisbon Expo was the ocean and the original Oceanario building designed by Peter Chermayeff was the centrepiece located in the middle of the marina. The building reads like typical expo/conference structures on the 1990’s. It has no connection to the waterfront around it. In the distance we get a glimpse of the Portugal Pavilion by Alvaro Siza, which looks like the antithesis of the Oceanario de Lisboa.

We eagerly walk to the pavilion slowly, wander beneath the sweeping concrete canopy and taking in the monumental scale of the space and materiality. After seeing the clumsiness of a ‘centrepiece’ with rubbish piled up beneath, it was a surprise to see a series of walled courtyards at the back of the Portugal Pavilion where the realities of a building viewed in the round could conceal and delight with shade trees, stacked furniture and bins. The visit to the expo site was concluded with a brief visit to Santiago Calatrava’s railway station before jumping back on the bus to lunch. As we departed we discussed the prevalence of nautical references in the architecture of the area and its similarities to architecture from the same era in Australia which we coined as ‘Noughties Nautical’.

Following lunch the walking tour by foot began with a journey through the city and up to the Castelo de São Jorge via a series of elevator links. Within the walled castle complex the tour takes us to an excavation that was discovered while preparing foundations for a new car park. Once uncovered the archaeologist discovered that the foundations revealed centuries of history from the Iron Age, mediaeval Muslim occupation and a fifteenth century palace. The excavation is surrounded by a Corten retaining wall that folds into the landscape and creates small covered areas to protect various elements. A white form floats over another part of the dig, which when entered recreates a series of rooms of former 11th Century Muslim domestic structures. This approach of dealing with history without the use of literal replication insinuate a sensitivity and subtlety towards place and materiality within Portuguese architecture.

During the remainder of the afternoon we meander through the extremely busy streets of the old city from the castle towards the waterfront. It is during this time that Rodrigo elaborates on the history of the city and the impact of an earthquake and subsequent tidal surge in the 1600’s that brought much of the city to the ground. In response to evacuation issues with the previous plan the city was rebuilt with wider streets improving access but also resulting in the uniform style of colourful and glazed tile buildings across the entirety of the old city.

Today the tour showed us a range of projects designed by local and international studios, which implied that Portuguese architecture is rational, confident and quiet. I’m now looking forward to a day of practice visits to hear if they describe their work in a similar way.

– Phillip Nielsen

Lisbon day 1: Perfect Imperfect

We arrived in Lisbon today, city three of three. A relatively light on itinerary we had only had three things to do. Make it to the airport on time, tour the Museum Art Architecture and Technology (MAAT), and eat a Portuguese tart.

We managed number one, relatively unscathed, although with Carrie’s birthday celebrations and the Eurovision final there were a few sleep deprived tour members on the bus. The flight over the Channel and beyond allowed time for reflection on what the tour so far and anticipation for what was to come, between naps that is.

Contrasts and similarities between Copenhagen and London were exacerbated by our arrival to Lisbon. Copenhagen was an amazing city and is regularly ranked amongst the top liveable cities on the world. On our studio visits and building tours we learned that people are always at the centre of the decisions made for the city, public places are of high priority to government and architects alike. London on the other hand had a more privatised approach to public space. Squares that seemed public were in fact private spaces that had commercial not community reason for being there. While London is seemingly all about monumental architecture, Copenhagen seems more humble. Still they both seem to be a bit contrived, maybe a little too perfect. But only in comparison to Lisbon.

Lisbon feels vibrant. The topography, hilly streets that wind around the city are filled with brightly painted buildings or beautifully glazed tiled facades. The pavements are made of patterned mosaic stones that have become polished (and a little slippery) by the constant footsteps of the cities inhabitants. The narrow streets will unexpectedly open up into beautiful public squares. There is an imperfection to the city, that in contrast is starting to make Copenhagen feel a little Truman-esque.

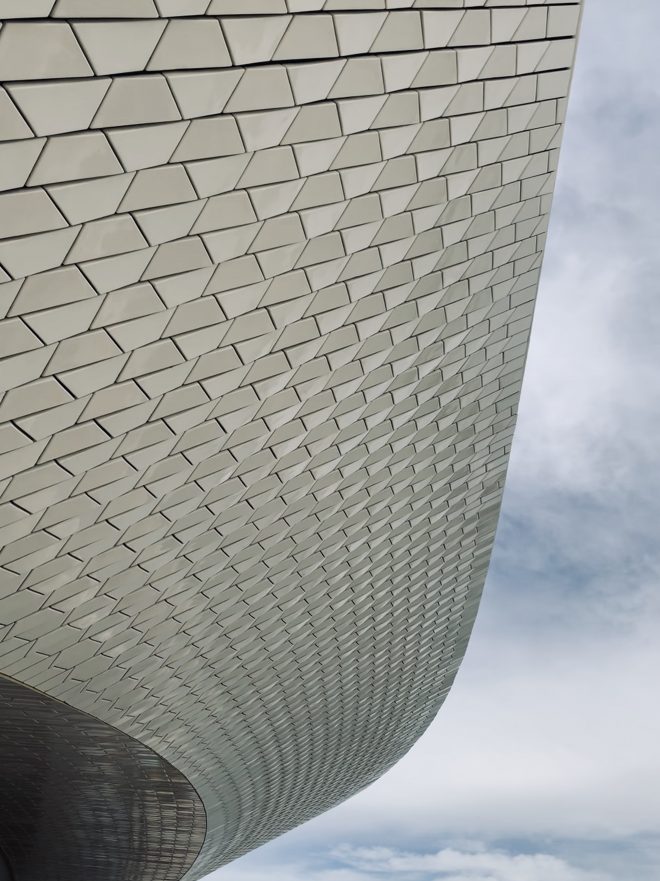

This imperfection of the city is somehow manifested in AL_A’s MAAT. Located in the historic Belem’s district the project, commissioned by the EDP Foundation a private non-profit institution, it seeks to revitalise the riverfront and provide a space for “debate, critical thinking, and international dialogue”. The building is pulled back from the rivers edge, giving way to a large promenade the is filled with people walking, cycling, and scooting by. The sculptural form of the building also provides a large open space on the roof top with 360-degree views of the river and the city. It’s making some fantastic civic moves. The form, when seen from particular angles, has beautiful lines that are reminiscent of the Sydney Opera House by Utzon. The execution is far from perfect though, and spatially the interior poses some problems in the operation of a museum gallery space.

Our museum guide Renato Santos introduces us to the concept of “real” and “fake” space. When clarifying if he means the “real” space is the architecture as it was originally designed and the “fake” space is the temporary insertions to make the current exhibitions workable in the building, he answers, “even fake things are real. Fake news is real to the people who believe it is real”. A highly philosophical answered, to what I thought was a pretty straight forward question. I’ll be thinking about that one for a while.

It is what he means though, and this need for “fake” space in a building designed as an exhibition space, shows how this building is not perfect. Servitudes – Circuits (Interpassivities) by Jasper Just in the Oval Gallery plays to this need for “fake” space by inserting new pathways and spaces into the building. The feeling is that without an imperfect exhibition space to do that in, the art work wouldn’t be as successful as it is.

The neighbouring exhibition Fiction and Fabrication: Photography of Architecture after the Digital Turn also speaks to the themes of perfection, imperfection, real, and fake. With the anniversary of 30 years of photoshop, it is hard to decipher which photos are real, what has been fabricated, and if being perfect makes them good images or not. Just as if being a perfect city, makes for a good city. I’m excited to find out more about Lisbon on our walking tour tomorrow and just how perfectly imperfect this city is. Since we never managed to get that Portuguese tart, we’ll have to work on that too.

– Carly McMahon

London day 3: Preservation in the age of capitalism

London day 2: Life on Mars

Day Five of the tour was, as usual, a rapid-fire affair. Our morning began at the Foster and Partners ‘campus’ in Battersea, which includes several model making areas, a to-die-for materials library and a thrumming café. The visit revealed the practice’s parallel interests in innovation, materials research and commercial viability. We all left suitably impressed.

By 10:30, we were in a taxi, racing across town to the sleek AL_A studio. Here, we were shown several of the practice’s projects, which employ everything from carbon fibre to crafted ceramics. Then lunch, then a swift tour of the accomplished White Collar Factory by AHMM, then a pit-stop at the London outpost of the Australian studio Hassell. We rounded out the day with a tour of Mars, But more on that later.

The pace of this tour has been quick, quick, quick – yet I couldn’t have hoped for a speedier education. Over these last five days, we’ve visited two cities and eleven practices who have generously opened their doors to our group of young, curious architects. We’ve been thirsty for knowledge – and quite often parched – as we’ve raced around these cities, keen and eager to learn.

While we’ve moved at lightning speed, our observations have accumulated – and solidified – more slowly. We’ve started to see trends in what is said – or not said – by each practice that we visit. By now, we’ve also experienced two cities, with two distinctive architectural cultures, and patterns are emerging.

Spending an hour at each practice to talk about their projects – and priorities – the patterns are illuminating, Overwhelmingly, the studios in Copenhagen spent their time discussing people and place. Their focus was undoubtedly drawn towards the greater project their own city, and how they’d use their tools and talents to improve it.

By contrast, London’s architecture scene has been underscored by intellectual, technical and professional ambition. In this fast-paced, global city, the outlook is international, multi-disciplinary and driven by an insatiable desire for excellence.

So far, this has manifested itself in all kinds of ways. It’s evident in the structural prowess of Rogers Stirk Harbour and Partners, and in the impassioned investigations of Peter Barber Architects. It’s also clear in the archive-diving work of 6a Architects, whose work originates in painstaking analysis.

For me, today felt like another stratosphere: moving through three (very) large practices was dazzling, and puzzling, and very foreign. Peering down on hundreds of monitors at Foster and Partners, I felt a long way from home and the realities of our small practice of three. At the same time, it was exciting, and exhilarating, to be amidst such an unfamiliar place. There was loads to learn.

Yet, across these practices, it felt like we spoke more about life on Mars than we spoke about life in London. In fact, two of the three practices we visited have experimental projects they are developing on the red planet, far away from earth. The best of these was Hassell’s enthralling Mars Habitat project, which mobilises inflatables and Martian dust to form a community for astronauts. Again, this was a world away from my daily work in Sydney.

Today, we heard more about architectural prowess than people or place, or this city we’re in. This is not to say that these practices don’t care about these other ideals – I’m sure they do. But, within our designated hour, we heard more about experimentation and technical excellence, and forging new frontiers.

Life on Mars? As the day drew to a close, I couldn’t help but wonder about life on Earth, and in this place. Across the universe, these are undoubtedly the places that concern me and our studio’s work.

Ultimately, hearing these things helped me – and everyone on the tour – start talking about what drives each of us: where we work, what we value, and what we think matters most. In many ways, this is what the Study Tour is all about: getting outside your comfort zone, challenging your assumptions, and figuring what you stand for.

– Jennifer McMaster