On the last sitting day before the federal budget and in the lead up to the next federal election, the Australian Institute of Architects hosted a Parliamentary breakfast in the nation’s capital. On Thursday 21 February 2019, National President Clare Cousins led an expert panel comprising Nicola Lemon, Chair of PowerHousing Australia and Denita Wawn, CEO of Master Builders Australia at Parliament House in Canberra. The panel, moderated by the Australian Financial Review’s Economics Correspondent Matthew Cranston, shared their perspectives on Australia’s housing affordability crisis for an audience of around 90 people including MPs, Senators and sector leaders.

Read National President, Clare Cousins’ presentation on the importance of partnerships and the role of architects in this critical and complex issue below.

Housing a growing nation

21 February 2019, Parliament House, Canberra

As you are all too aware, today is the last sitting day before the federal budget.

The spectre of the next federal election also looms large.

It’s extremely timely therefore that we stop and ask ourselves: what sort of nation do we want to build into the future?

I use the term build very deliberately.

This breakfast brings together organisations whose members provide homes for countless Australians.

For us, housing is our core business and affordability is of paramount concern.

Housing provides safety and security for people.

Housing is a basic human need and universal human right, and in the rapidly expanding cities and towns of the twenty-first century, there is a critical need for more flexible and diverse housing solutions.

Including here in Australia.

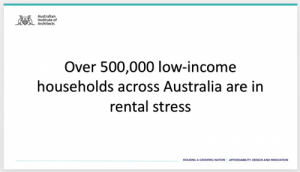

The affordable housing crisis in this country has deteriorated year on year and shows little sign of improving.

It’s a devilishly complex issue – and the lack of reliable statistics is part of the problem.

But our message here today is simple:

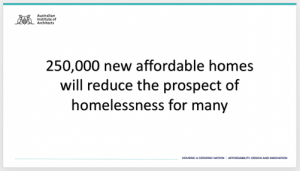

1. We need more affordable housing, much more

2. We need to ensure that this new affordable housing is of high quality

3. It will require investment, innovative ideas and financing solutions

And the only way we will succeed, is through partnerships.

Partnerships among industry, such as those here today.

And partnerships with government, at all levels.

Now I know many of you might be thinking “architects and affordability” – aren’t words that usually go together.

Allow me to set the record straight.

Architects have always been pioneers of new housing typologies, whose beneficiaries are predominantly those needing access to affordable housing options.

From Baugruppen in Germany to our own Australian grown version like Nightingale – in which I am a project lead – architects have pushed the boundaries using innovation and problem-solving skills.

For us, the first consideration is always quality.

Why?

Because housing is inextricably linked to health and wellbeing.

Good design delivers significant health sustainability benefits and increases the resilience and longevity of our built environment.

Look at the Millers Point in Sydney as a case in point “where 100-year-old original timber windows still operate perfectly” in premises originally intended for the city’s workers.

It is also critically important to create dignified spaces and living conditions.

And cost – while a convenient scapegoat to cite – is not an argument we will accept against pursuing good design.

Because the capital cost of a well-designed and well-built house or apartment is not much greater than the cost of a poor one.

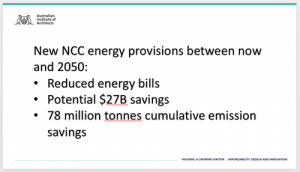

And you have to look past the purchase price because over the lifecycle of the building costs can be significantly less.

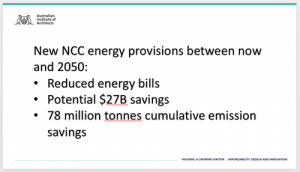

Architect-designed buildings are more energy efficient, cheaper to operate and easier to maintain and adapt.

For example power costs are approximately $25 per dwelling per month at Melbourne’s Nightingale 1.

This is critically important to affordable housing, because housing must be not only affordable to purchase or rent, but must be affordable to maintain and live in over the long term.

As I think Nicola and Denita would agree, we stand on the cusp of delivering a vast new wave of affordable housing in Australia.

We must ensure it is fit for purpose and will go the distance.

To date, the majority of affordable housing has either meant speculative, low-density detached housing or more recently, apartment blocks with low amenity and lacking the common spaces that promote a sense of place and foster connected and socialised communities.

Much of it lacks character, has poor thermal performance and accessibility for aging residents and very little of it will age well, or last long.

Or it is on the urban fringe, often without appropriate infrastructure in place, meaning residents have to commute long distances to workplaces and amenities.

Take the recent release of seven new suburbs in Melbourne.

This degree of urban sprawl is not sustainable.

Releasing comparatively cheap land on the market, miles from transport, services and other amenities fails the test of being truly “affordable”.

It is time for new solutions and better ideas.

And the first step is access to better data.

We have no nationally consistent, regularly updated dataset that can track housing needs – for any type of housing, affordable or otherwise.

Reliable, up-to-date statistics are needed to inform a national affordable housing strategy.

And we need a federal minister to oversee it.

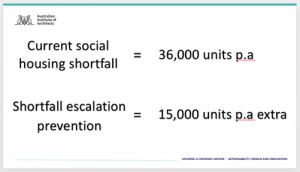

We do have some inkling of the magnitude of the task ahead.

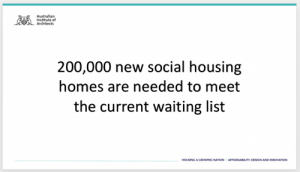

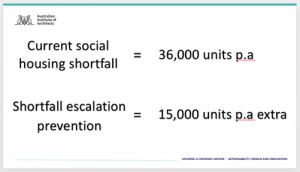

AHURI’s most recent report says we need to triple our social housing stock “over the next 20 years to cover both the existing backlog and newly emerging need.”

By their reckoning, 25 years of inadequate investment has left Australia facing a shortfall of 433,000 social housing dwellings.

The current construction rate – little more than 3,000 dwellings a year – does not even keep pace with rising need, let alone make inroads into today’s backlog.

So how do we turn this around?

Inclusionary zoning is one option.

Incentivising state and territory governments to mandate that major new developments include an affordable component could vastly increase supply.

Long-term leases of public land to private sector developers for peppercorn rent is another option.

In this case the public asset is retained and the developer no longer has to factor in the cost of the land in their rental price.

It’s clear that we need innovative financing models and big ideas to bridge one of the biggest barriers – yield gap and I know Nicola will speak on this.

Equally important is the need to maintain a dual focus on affordable renting and affordable home ownership.

We must help provide pathways to home ownership, like WA’s tremendously successful keystart program, with low deposit home loans starting at just 2% for eligible applicants.

Things like the emergence of a new Build-to-Rent asset class also have the potential to revolutionise the affordable housing experience for countless generations of Australians.

While affordable homes to buy are the ideal, Build-to-rent is an important part of the housing mix.

Built-to-rent incentivises developers to build higher quality, sustainable buildings as they have a vested interest in their longevity and minimising ongoing running costs.

Built-to-rent can create an opportunity for longer lease terms, which provides more stability and housing security.

It has worked well overseas with a proven track record now in the US and UK.

Built-to-rent couldn’t come at a better time as we face the twin challenges of a growing and ageing population.

Today more Australians rent than at any time in the last six decades. One in three, in fact.

And at the same time, the proportion of Australians aged over 65 has and will continue to increase.

Build-to-Rent also aligns with another key affordability policy priority – increasing density in the middle ring.

This is especially critical to meet the housing needs of key workers.

But Build-to-Rent needs government support to get established.

And, while it clearly has the potential to be an important part of the affordability equation, Build-to-Rent on its own won’t solve Australia’s affordability crisis.

The Institute, together with our industry partners and government, want an integrated, national strategy to map out Australia’s affordable and sustainable housing future.

And this must include community-led Indigenous housing.

We want a framework that is supported across the political divide, because we know all of you want what is best for Australians – and this can help.

We want the economic benefits to flow from the increased productivity and lower demand on health, social and welfare services that we know can come from stable affordable social housing investment.

Most importantly, we need to constantly remind ourselves who we are doing this for – not ourselves or even necessarily our children, but the generations that come after them.

And some of the hardest working and most vulnerable among them.

There’s more than one school of thought that says a nation’s people are its greatest asset.

We need to look after them and housing is integral to that.

We don’t expect you to fix this on your own. Just like we don’t expect developers to, or Community Housing Providers to do all the heavy lifting.

But we do ask you to step up beside us and work in partnership.

To have the courage to try new models.

The guts to make major public investments.

The commitment to aim for better outcomes for the people you have the privilege to represent.

We know you care deeply about this issue and we thank you for coming to this event.

Thank you.