Sadly, today marked the final day of an absorbing ten days on tour. A few short hours after celebrating our final night together, we each climbed on a bike for a guided tour with local architect and university lecturer, Carlo Berizzi. His fascinating tour outlined to us the city’s history, disasters and new directions.

In 2010, the city of Milan announced its exciting new vision for the future. The goal was to become a modern international tourism city, identifying key strategies such as “The Clean Water project,” “The Green Ring project” and the construction of a collection of new museums. Since this time, the city has built ten new museums including the Foundation Prada, Alpha Romeo and the Kartell Museum. It has transformed itself from its post-war industrial beginnings into a cultural hub. Further to this, Milan has developed a masterplan to respond to undeveloped pockets of industrial land as a means to achieve its grand vision for its city: 88 Cities. The concept offers 88 unique cities or suburbs to Milan, creating living options for a thriving and diverse city, simultaneously reducing the city’s urban heat island effect and improving its ecology.

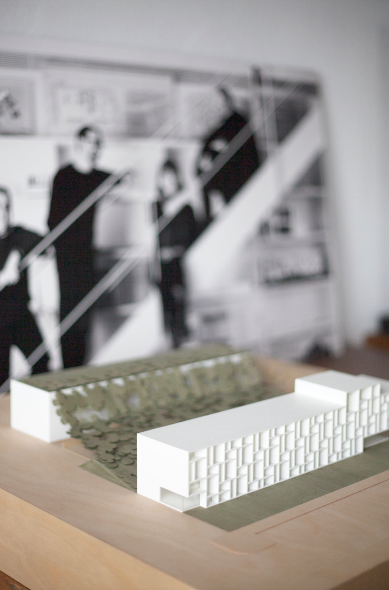

Today, we visited one of the 88 new “cities” called City Life. This masterplan was devised by Daniel Libeskind, Arata Isozaki and Zaha Hadid and aims to encourage open space, remove cars and centralize retail facilities. The masterplan, conceived of high-density residential, office and retail buildings, is more in line with modern international ideals than the intricacies of neoclassical and postmodern architecture of Italy.

The government-driven masterplan relies upon private sector implementation and has resulted in huge apartments with above average sales prices, aimed at an international market that is taking a long time to arrive due to a number of factors. For example, the office tower by Zaha Hadid Architects has failed to attract tenants and is currently empty. As a result, the future appears unstable. This type of gated community has also detracted from a sense of community and connection.

We were also treated to several modern, post-war housing models by Gio Ponti among others, which combined shimmering tile clad facades with ideals of flexible planning. This resulted in organic, yet cohesive aesthetic that spoke of the people that lived in them, adding cultural richness to the buildings neighbourhoods. These typologies highlighted the change in building procurement since Italy’s turbulent political era of the 90s.

Learning of Milan’s bold new direction left an impression of optimism and possibility, highlighting Milan’s commitment to remain relevant leader in Europe’s future. However, Milan appears to have been affected by the countries political turbulence of the 90s that saw its development fall behind its European neighbours. The recent push for development, as admirable as it appears at the surface, seems to be a desperate attempt to make up for lost time. The city has looked outward rather than inward to implement its vision, and in the process has undermined what made it so fantastic in the past – its people.

The trip drew to a close, bringing an end to long days of countless conversations and debates about the architectural possibilities we had been exposed to over the past weeks. Right now, it’s difficult to draw finite conclusions about how this trip will influence our thought process and our practice of architecture. It has, however, instilled an optimism about the quality and rigour of architecture in Australia and the opportunities we have – a polarizing realization that would not be possible, if not for the tour.

I cannot wait to catch up with the crew after some much needed sleep and a few weeks to digest the smorgasbord of architecture that we have just consumed. Don’t miss the final addition to the blog post series from Dulux – written by self-proclaimed “normal human,” Alison Mahoney – with a different perspective of the tour.

– Jason Licht

Follow #2018DuluxStudyTour for updates.